That the object of his desire was a Muslim woman was telling. His character had in fact been seduced by the Middle East, for all its complexities, which is a far cry from the usual American denial of showing how "our" boys are suffering in one of those wars instead of asking why they're actually there in the first place.

Films like The Hurt Locker.

In fact, a salient but understated point Scott makes is that the Middle East has an erotic charge about it, and it's worth investigating that, along with all the other geopolitical considerations.

Once people start falling in love across races, cultures and religions life becomes infinitely more interesting - and complex. On a micro-scale, you can't get more political than getting married.

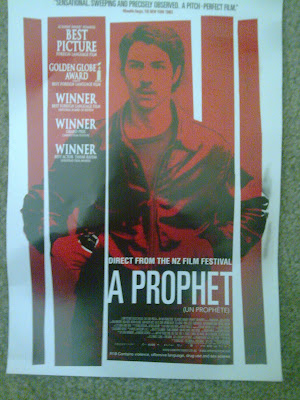

But in the two films under discussion today there is no love lost, let alone glimpsed or even desired. In the first, A Prophet, which won the Grand Prize of the Jury at Cannes, a Bafta, the Golden Globe and has been rightly nominated for a foreign Oscar, there is a warning, a cautionary.

What makes it so powerful is that Malik (Tahar Rahim) is a nonentity when Jacques Audiard's film begins. The only thing that distinguishes him from other French people is that he speaks Arabic, but he comes from the streets. He has no parents, no political or religions affiliations.

But the first criminal and symbolic act he has to perform for the Corsican mob inside is kill an Arab - who might snitch on them - to ensure his own safety. This is virtually the only time we see him feeling anything, not because the man is an Arab, but because Malik is not a killer. So he does what has to be done, but then that man comes to "visit" him thereafter, to guide him, mentor him, praising God.

Though a very long movie, the shift from Malik's complete subservience to utter power in six years is almost imperceptible, his face showing very little again.

And if the implicitly Catholic mob, as represented by Niels Arestrup's obscenely brilliant prison don, are always violent towards Malik, then the Muslims offer him something that is central to their faith. Family. And I don't mean the family of man, or men, I mean his friend is dying of cancer and offers Malik his beautiful wife and child. What street urchin would say no?

So if ever there was an allegory on how Islam became radicalised, this is it. It's very scary, and very necessary.

On completely the other end of the scale is Chris Morris's scathing satire Four Lions. Note, it is not a comedy, it is a satire, which means it is there to highlight the absurdities of something. In this case it is a quartet of blithering, fundamentalist Muslims idiots with Sheffield accents.

Using all the techniques of farce and slapstick, Morris sends up some of their more ridiculous ideas, often using news-like camera zooms.

On a domestic level, when the imam comes to visit the leader of the revolutionaries, Waj (Kayvan Novak), he has to shield his eyes from seeing Waj's (very beautiful) wife, Sophia (Preeya Kalidas). The scene ends up in a suburban water-pistol fight between the married couple and their imam because he finds it repulsive to be in the same room as a woman, but otherwise he's a peaceful sort who doesn't intend blowing people up.

Sophia, however, discusses her husband's martyrdom as if they're planning a Sunday morning picnic.

Extremism takes a knock, literally, when Barry (Nigel Lindsay) suggests they should blow up a mosque so that they can radicalise and mobilise more Muslims. Waj says that is akin to hitting yourself and finally persuades Barry to do just that, giving himself a blood nose.

But always there is the reality that bombs are bombs and they can completely spoil your day and, even though Morris only half covers himself from a fatwa by showing just how stupidly dogmatic the English are as well, one wonders what Muslims would think of this film. Would they laugh as much as Westerners? It would be interesting.

On a purely formal level, this outrageous flick starts losing steam towards the end, but it has more laughs in it than most Hollywood comedies put together anyway.

And then there is the question of who has the last word. The satirist or the historian? It is quite conceivable that the latter might one day come to the disturbing conclusion that the man who almost single-handedly dragged Islam into the spotlit glare of global scrutiny, George W Bush, was also a blithering, fundamentalist idiot.

Neil Sonnekus