Teenagers, according to the October edition of National Geographic, will do almost anything to impress their peers, including risk their lives.

This we know, but the reason proffered is that they’re investing in their future. After all, they’re going to spend more time with their friends as time goes by than with their parents.

Come to think of it, they already do. Home is where they eat, sleep, facebook (v.) and get their washing done.

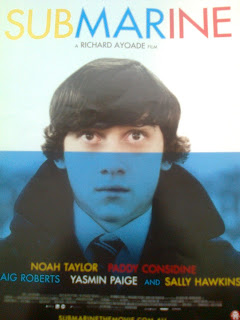

So when Oliver Tate (Craig Roberts) wants to keep his parents’ little nuclear family unit intact in a small Welsh town, it’s not so much out of love as self-interest.

Hell, home does have its uses. You can, for example, lose your virginity there while mum is giving her New Age ex a handjob on the beach.

Dad (Noah Taylor) is a marine scientist who is as excitable as those squids in which he takes such a keen interest. Ma is all submerged Eighties passion and played by Sally Hawkins, who could act a soup can and make it interesting.

If the plot of Submarine is predictable (boy meets girl, loses girl, gets girl back) then it is done with typically quirky Anglo understatement that is, initially anyway, very funny. But after a while I started sensing an older (sensitive, self-deprecating) writer behind this teenage wannabe intellectual.

And really, how many more of these do we have to endure? Could we stop having so much of this parochial me stuff (the film is executive produced by Ben Stiller) and a little more teen spirit? A little more revolution?

***

If you hadn’t heard of the German choreographer Pina Bausch (I hadn't) then you’ve probably heard of Wim Wenders (if you’re over a certain age and/or of a certain disposition). Wenders, of course, is the maker of the masterful Buena Vista Social Club.

Bausch, who died in 2009 at 68, tried to find new ways of expressing oneself through dance, much as Wenders et al tried to find new ways of telling stories that didn’t reflect the above, very Americanised, plot.

Her work is quite obsessive, quite grim, occasionally joyous, but never predictable. Nor is it fashionably anti-male, though the one dance in which a group of men grope a woman on every part of her body except her privates makes the metaphor of rape perfectly clear. If she loved men deeply it doesn’t mean she was blind to their faults.

Wenders has taken the dances public: they are no longer confined to the Wuppertal Tanztheater, which Bausch ran, though she might have taken the dances on to the streets as well. So you can see a beautiful dance take place at a quarry, beneath a monorail or in a glass hall in a forest to some very interesting music.

When the dancers talk about Bausch we hear what they say and see them reacting to what they’re saying, which has a rather interesting effect.

Pina is a slightly long documentary, but it is never boring. If it lacks humour then it is still a celebration of that thing which happens between men and women, and it shows us that Bausch did so with a constantly questing, unflinching honesty.

Neil Sonnekus

Tuesday, November 29, 2011

Friday, November 18, 2011

Replaying Old Debts

The Debt has been marketed as a Nazi-hunting thriller, which has been done quite a few times before, sometimes good, often bad.

But it’s got the likes of Helen Mirren, Tom Wilkinson and Ciaran Hinds in it, the latter once again playing a doomed Mossad agent as he did in Munich.

Furthermore, the film is a remake and even the trailer for the remake of The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo looked pretty pointless, the titular “girl” looking completely wrong compared with the real “thing”.

But this is a remake of an Israeli film, Ha-Hov, which is unusual, and it’s directed by John Madden, who is not exactly a lightweight, whatever one might think of films like Shakespeare in Love and Mrs Brown.

Moreover, it has three very interesting (and attractive) new actors in it, Californian Jessica Chastain, Kiwi Martin Csokas and Australian Sam Worthington as the younger versions of the more senior actors above.

What’s it all about? Back in the mid-Sixties three Mossad agents tried to abduct a Nazi from East Berlin and take him to Israel to stand trial. In the present the one agent’s daughter has published a book on that heroic episode and is very proud of her mother, Rachel (Mirren).

But it’s not quite as cut and dried as that. Switching back and forth between two eras, one of the things the film effectively shows is how passion, beauty and ideals can fade into bitter, recriminatory middle age, as symbolized - among others - by the angry scar on Rachel’s face.

The three younger actors do a brilliant job of playing agents holed up in an apartment in communist East Germany, looking after their Nazi captive. The paranoia and sexual tension is palpable and the horrible truth is that they have become their captive’s captives, which he milks to its violent extreme.

The beauty of the story is that its marketing will have attracted many of those who might want to see a very watchable, sensual but safe historical thriller. They might be in for a surprise, for with Biblical simplicity and ingenuity The Debt is not so much about redressing past injustices perpetrated against Jews as it is a sobering allegory on Israel’s very troubled present.

Neil Sonnekus

Friday, November 11, 2011

Do Not Touch

Steven Soderbergh is a producer’s dream: he brings his movies in on time and budget.

He makes films like the commercially successful Ocean’s franchise and in turn makes more arty film like Kafka, which I haven’t seen, and The Limey, which I did. It sank like a stone, but that’s probably because it’s a very intelligent meditation on revenge, using some intriguing editing techniques.

The man is clearly no fool. Hell, some of his movies even manage to combine commerce and message, as in the “iconic” Erin Brockovich, which had a nice feminist and topical public health angle to it.

And now there is Contagion, which tries to combine the latter two films, and some. Marketed as a thriller, it is also an industrial flick, which shows us just how a disease spreads. And it's a music video - to keep the beat going for that long, initial section where people all over the globe are attacked by this invisible thing and not much dialogue is required.

Borrowing heavily from Hitchcock, le directeur also quickly dispatches of a heavyweight leading lady or two, in one case showing us just how pretty - Cronenburg-like - the inner flap of her skull might be. One woman in the cinema almost choked on the popcorn she was so loudly munching, which kind of made up for the loss of an actress who has a very sexy voice and is married to a singer from a terrible band.

Anyway, if Matt Damon plays the new Mr Reliable after the semi-retirement of Harrison Ford, then he isn’t really given much with which to work and the hero of the story is, refreshingly, an unassuming scientist. Jennifer Ehle plays her quiet character to perfection – and she doesn’t have much to work with either.

This is the second time Soderbergh has worked with Damon and writer Scott Z. Burns; their previous outing was The Informant! a slow, droll corporate comedy that involved a lot of cellphone calls and meetings in boardrooms. So too this film, which becomes a little boring after a while, even if it is only a very considerate 106 minutes long.

But we persevere because Oscar Wilde said the next war would be fought with test tubes, even though the film’s premise is paradoxical. On the one hand it’s saying we must be very, very afraid of who and what we touch, on the other it doesn’t want to freak us out too much, so it shows us how clever and brave one scientist (working in America, of course) is.

Neil Sonnekus

* Next week there will be a review of the exceptional The Debt, starring Helen Mirren, a passionately intelligent meditation on the nature of revenge and lies in the troubled land of Israel.

** The photograph above is not from Contagion but from the TV series Downton Abbey. Early-20th century England suddenly became postmodern New Zealand. The photograph was taken with my cellphone off the TV set. Series three has already been commissioned.

He makes films like the commercially successful Ocean’s franchise and in turn makes more arty film like Kafka, which I haven’t seen, and The Limey, which I did. It sank like a stone, but that’s probably because it’s a very intelligent meditation on revenge, using some intriguing editing techniques.

The man is clearly no fool. Hell, some of his movies even manage to combine commerce and message, as in the “iconic” Erin Brockovich, which had a nice feminist and topical public health angle to it.

And now there is Contagion, which tries to combine the latter two films, and some. Marketed as a thriller, it is also an industrial flick, which shows us just how a disease spreads. And it's a music video - to keep the beat going for that long, initial section where people all over the globe are attacked by this invisible thing and not much dialogue is required.

Borrowing heavily from Hitchcock, le directeur also quickly dispatches of a heavyweight leading lady or two, in one case showing us just how pretty - Cronenburg-like - the inner flap of her skull might be. One woman in the cinema almost choked on the popcorn she was so loudly munching, which kind of made up for the loss of an actress who has a very sexy voice and is married to a singer from a terrible band.

Anyway, if Matt Damon plays the new Mr Reliable after the semi-retirement of Harrison Ford, then he isn’t really given much with which to work and the hero of the story is, refreshingly, an unassuming scientist. Jennifer Ehle plays her quiet character to perfection – and she doesn’t have much to work with either.

This is the second time Soderbergh has worked with Damon and writer Scott Z. Burns; their previous outing was The Informant! a slow, droll corporate comedy that involved a lot of cellphone calls and meetings in boardrooms. So too this film, which becomes a little boring after a while, even if it is only a very considerate 106 minutes long.

But we persevere because Oscar Wilde said the next war would be fought with test tubes, even though the film’s premise is paradoxical. On the one hand it’s saying we must be very, very afraid of who and what we touch, on the other it doesn’t want to freak us out too much, so it shows us how clever and brave one scientist (working in America, of course) is.

If the virus were to continue its trajectory it would wipe out about 70 million people, which is a lot, but nothing if you think that we’ve just reached the 7 billion mark. And who’s the antagonist here anyway? The virus? The somewhat nutty blogger (Jude Law doing a kind of crytpo-Julian Assange number), saying it’s a conspiracy, it’s just the pharmaceutical companies trying to make more money? The companies themselves?

No, dear friends. We in the West must get rid of all bugs, for they serve no purpose, and we really mustn’t touch those darned Chinese, whence all diseases come.

Neil Sonnekus

* Next week there will be a review of the exceptional The Debt, starring Helen Mirren, a passionately intelligent meditation on the nature of revenge and lies in the troubled land of Israel.

** The photograph above is not from Contagion but from the TV series Downton Abbey. Early-20th century England suddenly became postmodern New Zealand. The photograph was taken with my cellphone off the TV set. Series three has already been commissioned.

Thursday, November 3, 2011

Whining and Dining

Film, by its very plastic nature, lends itself to playing with the space/time continuum.

It can jump from one era or reality to another just like we can believe that someone closing their front door at home and then walking into their office across town is continuous because all the stuff in between is superfluous, boring and implicit anyway

There have been some very good and many abominable films playing with these elements. One that truly milks the medium intelligently is David Cronenburg’s eXistenZ, in which one soon has no idea what is “real” and what is video game anymore – and that’s only one of the reasons why it’s good.

On the other hand, you have something like the horrendous Déjà Vu in which Denzel Washington as an FBI agent travels back in time to save a woman and, of course, falls in love with her - without the slightest hint of irony.

Someone had to send all of this up and who else but Woody Allen, who might well have found his alter ego in the pouting Owen Wilson. If the two don’t exactly look like each other (across the space/time continuum), they do have about the same pitch when they whine - and does Wilson's Gil whine in Midnight in Paris.

Then again, he does have plenty to whinge about. First of all, he’s a successful Hollywood scriptwriter, which is enough to depress anyone. Secondly, he’s got a bad novel with which he’s stuck. But he has a beautiful fiancée, Inez (Rachel McAdam). On the other hand, her parents, who they’re accompanying to Paris, are rabid Republicans.

Then, just to crown everything, they bump into Inez’s professor friend Paul (Michael Sheen) and his virtually mute wife. Like so many academics, the man’s not only in love with his own voice, he also thinks all the world’s a lecture hall.

So you can’t exactly blame Gil for being bored, irritated and restless. He wants, not quite as convincingly as his writer/director perhaps, to stop being an American. He wants to experience Paris for itself, not through the brash, daytime eyes of an American.

The main character here, of course, is the city itself. This is not a Paris with any social problems, though the American ones are rattled off by Paul, lest Allen be accused of having no social conscience whatsoever. But it is a perfectly convincing ode to a city, a love song whose premise is that the city is more durable and magical than its problems.

It is, as Gil says, quoting Ernest Hemingway, a moveable feast - and this is where most critics stop discussing the plot because Gil’s discontent with the present is so profound that he ends up, seamlessly, in the Paris of the 1920s!

That “really” is the young Hemingway, played very convincingly by Corey Stoll, drinking wine and talking about death without adjectives. They’re all there. Scott and the insecure, talented and suicidal Zelda (Fitzgerald). Cole (Porter). Gertrude (Stein). Pablo (Picasso). Among others.

And Gil, dressed in the usual writer’s uniform of ill-fitting trousers, a dull tie and check jacket in 2010, fits perfectly into the era!

Allen is clearly tired of everything that America or American film stands for, and if his Christina Vicky Barcelona was laced with Hispano clichés, then his praise song to Paris is laced with much better ones.

Carla Bruni does a perfectly natural tour guide and Lea Seydoux as a young shop assistant oozes unassuming charm. So, not only can the old guy still make a gently funny film with not a drop of overt violence or invective in it, but having removed himself from the equation he finally makes his women – and their city of light - glow.

Neil Sonnekus

It can jump from one era or reality to another just like we can believe that someone closing their front door at home and then walking into their office across town is continuous because all the stuff in between is superfluous, boring and implicit anyway

There have been some very good and many abominable films playing with these elements. One that truly milks the medium intelligently is David Cronenburg’s eXistenZ, in which one soon has no idea what is “real” and what is video game anymore – and that’s only one of the reasons why it’s good.

On the other hand, you have something like the horrendous Déjà Vu in which Denzel Washington as an FBI agent travels back in time to save a woman and, of course, falls in love with her - without the slightest hint of irony.

Someone had to send all of this up and who else but Woody Allen, who might well have found his alter ego in the pouting Owen Wilson. If the two don’t exactly look like each other (across the space/time continuum), they do have about the same pitch when they whine - and does Wilson's Gil whine in Midnight in Paris.

Then again, he does have plenty to whinge about. First of all, he’s a successful Hollywood scriptwriter, which is enough to depress anyone. Secondly, he’s got a bad novel with which he’s stuck. But he has a beautiful fiancée, Inez (Rachel McAdam). On the other hand, her parents, who they’re accompanying to Paris, are rabid Republicans.

Then, just to crown everything, they bump into Inez’s professor friend Paul (Michael Sheen) and his virtually mute wife. Like so many academics, the man’s not only in love with his own voice, he also thinks all the world’s a lecture hall.

So you can’t exactly blame Gil for being bored, irritated and restless. He wants, not quite as convincingly as his writer/director perhaps, to stop being an American. He wants to experience Paris for itself, not through the brash, daytime eyes of an American.

The main character here, of course, is the city itself. This is not a Paris with any social problems, though the American ones are rattled off by Paul, lest Allen be accused of having no social conscience whatsoever. But it is a perfectly convincing ode to a city, a love song whose premise is that the city is more durable and magical than its problems.

It is, as Gil says, quoting Ernest Hemingway, a moveable feast - and this is where most critics stop discussing the plot because Gil’s discontent with the present is so profound that he ends up, seamlessly, in the Paris of the 1920s!

That “really” is the young Hemingway, played very convincingly by Corey Stoll, drinking wine and talking about death without adjectives. They’re all there. Scott and the insecure, talented and suicidal Zelda (Fitzgerald). Cole (Porter). Gertrude (Stein). Pablo (Picasso). Among others.

And Gil, dressed in the usual writer’s uniform of ill-fitting trousers, a dull tie and check jacket in 2010, fits perfectly into the era!

Allen is clearly tired of everything that America or American film stands for, and if his Christina Vicky Barcelona was laced with Hispano clichés, then his praise song to Paris is laced with much better ones.

Carla Bruni does a perfectly natural tour guide and Lea Seydoux as a young shop assistant oozes unassuming charm. So, not only can the old guy still make a gently funny film with not a drop of overt violence or invective in it, but having removed himself from the equation he finally makes his women – and their city of light - glow.

Neil Sonnekus

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)